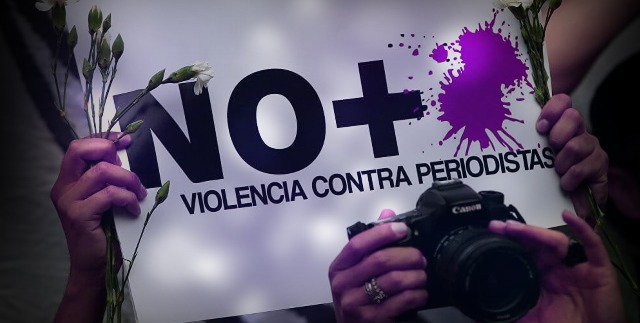

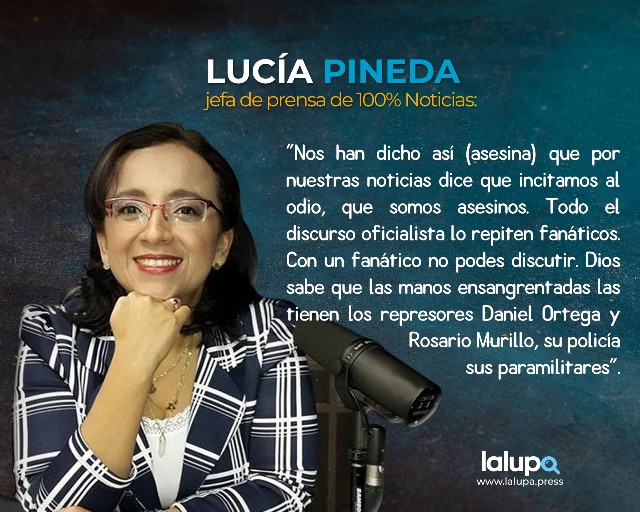

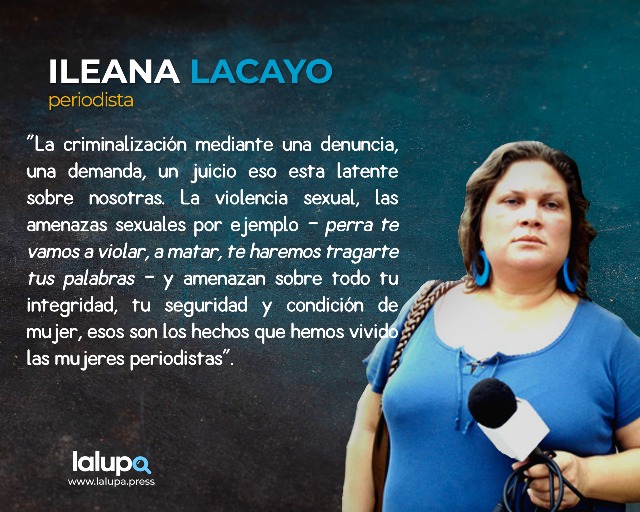

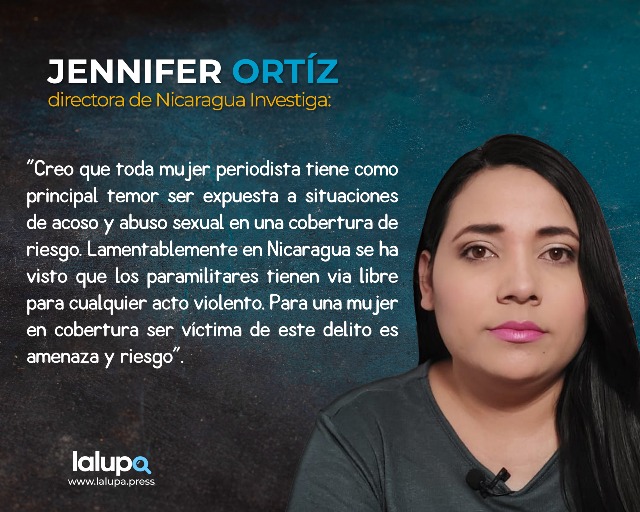

Women journalists attacked because of their gender and for practicing freedom of press

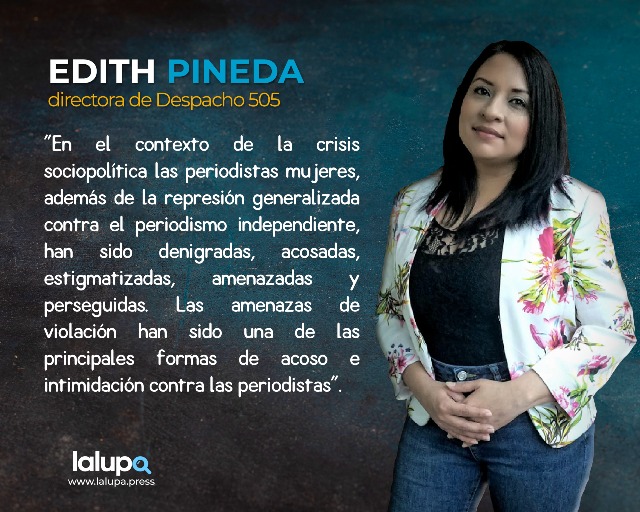

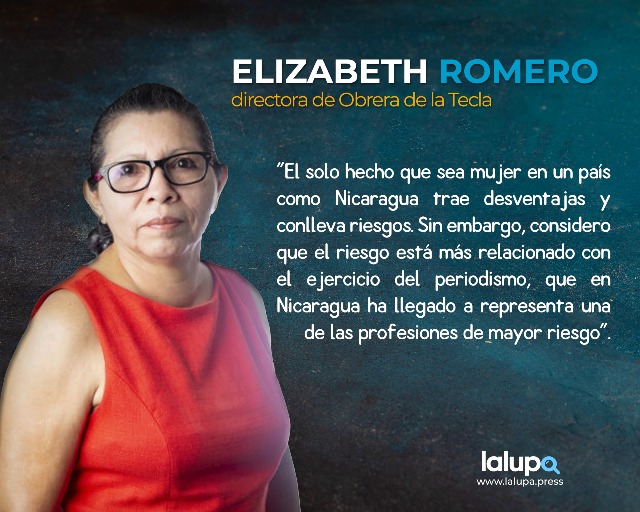

In Nicaragua being a journalist entails risk, but being a woman and a journalist is an additional risk not only for the professional herself, but for her whole family including children.