344 suicides in 2020: The highest figure in the last decade in Nicaragua

"We have learned that traumas are not meant to be worked on, they’re just to be swallowed” says expert who indicates the multiple causes of suicide

"We have learned that traumas are not meant to be worked on, they’re just to be swallowed” says expert who indicates the multiple causes of suicide

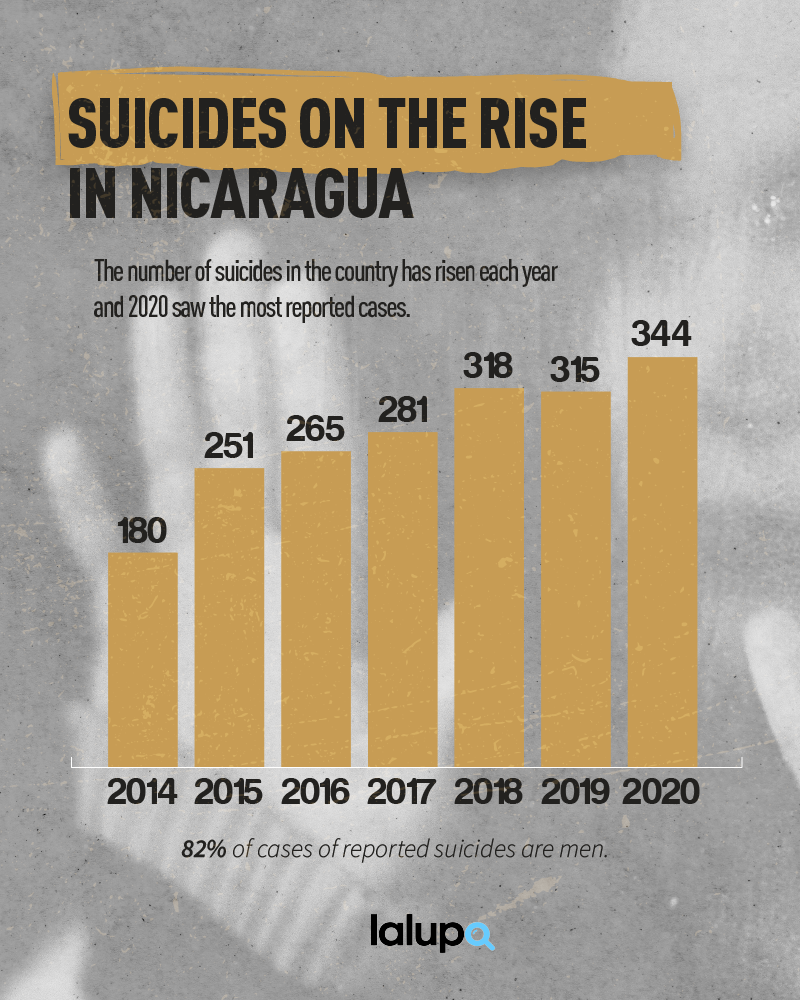

Nicaragua is a country of unhealed grief, where people have been unable to work on their life histories and are carrying the burden of generational and collective traumas says the social psychologist Martha Cabrera. She explains that because of this, many people dealing with depression, addiction and a disconnection with life end up committing suicide.

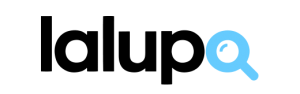

Since 2014 the suicide rate in Nicaragua had been rising, but the socio-political crisis that began in 2018, combined with the COVID-19 pandemic has sharply increased the population’s mental health problems. So much so that last year, according to the statistics of Ortega’s Police, there were 344 cases of suicide. The figure may even higher, according to the healing collective Sanar Nicaragua, since the way police figures are established is neither exact nor transparent.

“Suicide shouts out the pain of living. Because people are staying silent and swallowing everything, suicide represents a scream that cannot be expressed. This is rooted in several factors and you have to look at the whole panorama in order to understand it. It shouldn’t be seen as having only one cause”, Cabrera says.

On a regional level the Pan-American Health Organisation (PAHO/OPS) estimates in its third report on mortality by suicide that 79 % of suicides in the Americas are by men and represent the third cause of death for people between 20 and 24 years old.

The World Health Organisation (WHO/OMS) states in its World Suicide Report that more than 700,000 people killed themselves in 2019, that is, 1 in 100 deaths on a world level is due to suicide. In addition, while the global suicide declined by 36%, between 2000 and 2019, in the Latin American region they increased by 17%.

According to the WHO “suicide is an important public health issue, but often one that’s neglected, surrounded by stigmas, myths and taboos”. They’re often preventable with timely evidence-based interventions at a low cost.

Cabrera considers that suicide’s root causes lie in a series of factors that haven’t received attention and she analyses this from a historical perspective that involves the country’s history, people’s family histories as well as personal histories.

“The writer William Ospina said that Latin America has three wounds: from colonisation and genocide; from independence and the civil wars that came after; and from development that placed us as a poor country. I think that the country’s grief comes from there. They are experiences of grieving that we haven’t healed that we’ve merely silenced. We are a wounded country”, she says.

After these three wounds comes another historical phenomenon that has healed and still affects people today: war. Cabrera differentiates Nicaragua from other countries experiencing war in the region in that in Nicaragua no work was done on memory and there was no Truth Commission. This meant that people paid no attention to their collective traumas, something which has damaged the country’s social fabric.

“Nicaragua is a country without memory. After the war people just carried on working and pretended that the war never existed. This is how we learned that traumas are not meant to be worked on, they’re just to be swallowed”, she explains. This leads to generational trauma, since people grow up with traumatised mothers and father, and with a family history that has not healed.

The same thing occurs with the violence and sexual abuse that a majority of the Nicaraguan population has experienced. These are not worked on because of the taboo that surrounds these issues. Cabrera indicates another cause as the capitalist economic model, because this mode of production means that people don’t have a sense of belonging to the living world and often are traumatised by poverty and the different needs elated to economic suffering.

Forensic psychologist Marvin Mayorga, points to how the socio-political crisis has duplicated suicidal ideas among people across the country, and has worsened people’s mental health. Some of the people most affected are those who already have had histories of violence that they’ve not processed and those who have already had suicidal behaviours without receiving any support.

However, those who didn’t have previous trauma in their childhood developed it with the crisis, because they feel constantly persecuted and don’t perceive a hopeful future. Suicidal ideas also became more entrenched with the economic and labour instability that increased in 2018.

Psychologist Winy Martínez says that people who see suicide as the only option lack the psychological tools necessary for self-care and self-management that can be development with work on traumas.

“We’re experiencing a situation in which human rights practically don’t exist. When people don’t have access to many of these rights, they feel psychologically and emotionally threatened and violated every day”, Martínez explains.

Mayorga adds that the pandemic was a ‘behavioural stresser”, because when people are forced into staying at home this increased different forms of violence, especially against women, and produced crises between younger people and their parents.

“If we had double the usual levels of behavioural stress with the crisis, this doubled again with the pandemic. The pandemic not only affects health, but also many people became unemployed. On finding themselves without work, without money, without food, and facing increased levels of violence the conditions for people to develop suicidal ideas are accelerated”, he says.

The World Health Organisation has also declared that the pandemic is having a huge impact of people’s mental health, since they’re experiencing the loss of loved ones, increased suffering and stress, and quite possibly this has meant that a greater number of people are dealing with depression.

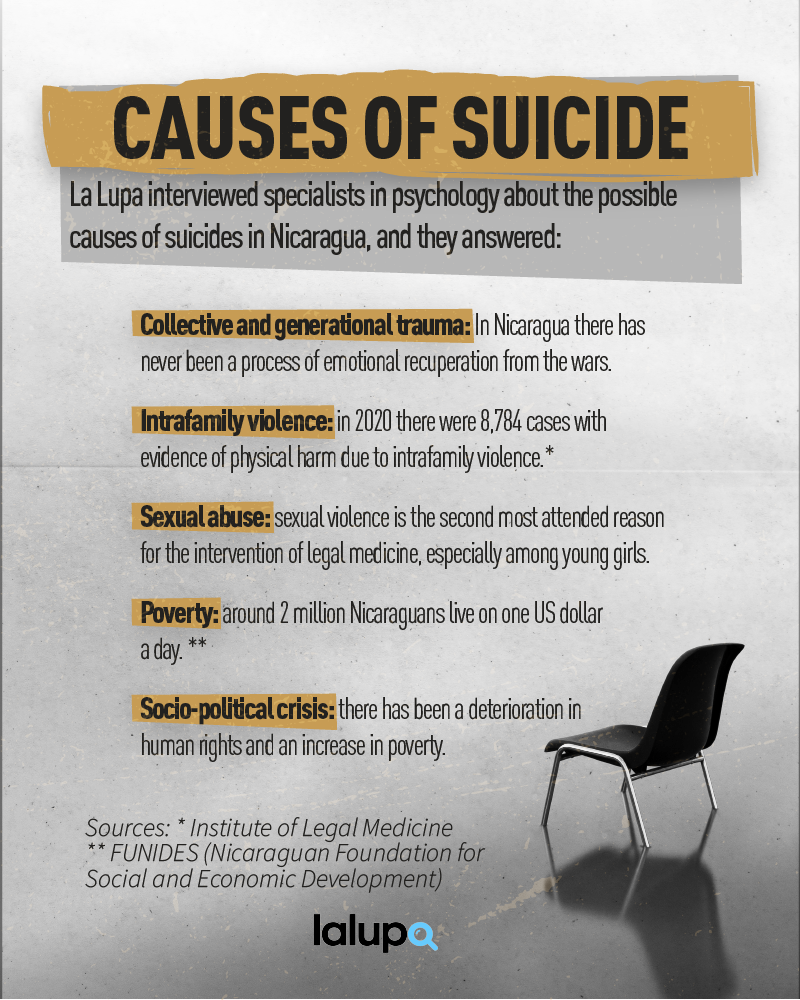

Mental health is only mentioned as a three paragraphs appendage in the Health Ministry’s Multiyear Health Plan 2015-2021. Nothing concrete is presented about how to attend to and improve the country’s mental health situation, and Integrated Attention for Addictions is only mentioned briefly. There is no plan for suicide prevention or an emergency helpline where people could ask for help.

A psychologist and member of the Sanar collective who wishes to remain anonymous states that one of the observations she’s made while accompanying people is that the majority suffer from anxiety, disturbed sleep such as night terrors or nightmares, feelings of desperation and thoughts about the lack of hope, all of which are signals of alert activated in the body that indicate experiences of trauma.

Due to all of this, she explains, Nicaragua is in the midst of a very adverse historical moment that makes it more difficult for people to heal their traumas and resolve problems, because there is no space for self-containment and the country’s only mental health centre can’t keep up with the demand it has from its high numbers of patients.

“Mental health services are really having trouble in the country. The psychosocial hospital is a reference point for the Pacific and Central regions of the country and they don’t have the capacity for containment due to the high demand for services” she states.

The last time the Health Ministry (MINSA) shared its budget for the José Dolores Fletes Psychosocial Hospital was in 2019. In 2015 it revealed the investment was only 0.8% of the annual health budget.

“The general law on health establishes MINSA as the regulatory body that is also responsible for health across the country, because it is a constitutional and human right and must be a central priority, and mental health as well” Mayorga says.

Mayorga states that MINSA is obliged by law to implement a plan for suicide services and prevention, especially given the alarming figures, but he says, the state has no interest in doing so.

A suicide prevention plan should be part of the National Health Programme and include educational talks in schools and universities, communications pieces on television and radio, with an aim to change awareness, attitudes and practices, as well as establishing a free helpline for people having suicidal ideas that enables them to phone and seek support. A plan like this should also include follow-up with the families of people who have committed suicide, due to the complexity of the grieving process for them.

The psychologists explain that people with suicidal ideas usually show a series of signs that can be easily identified. These include explicitly suicidal phrases such as “I don’t want to live any more” or phrases that damage a person’s self-worth such as “I’m totally useless”.

Other signs can be sudden mood changes, constant despondency or expressions of hopelessness, isolation, irregular sleep patterns, getting rid of much loved possessions, addictions and/or self-inflicted aggression on the body such as self-mutilation.

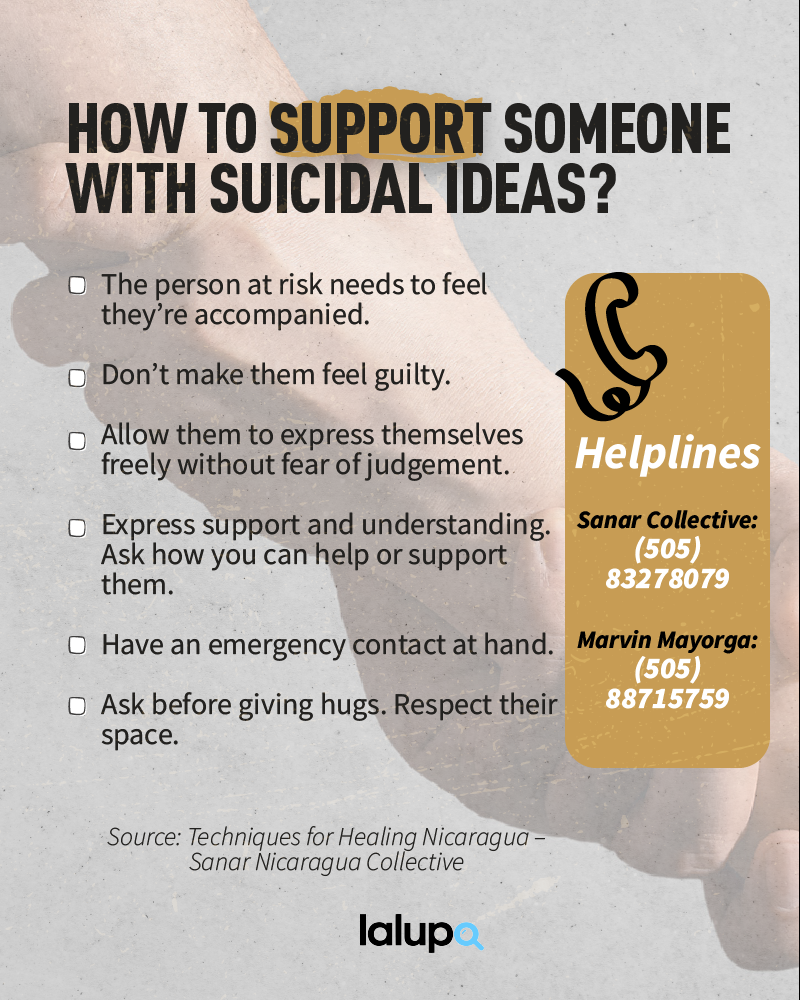

Mayorga indicates that the best way to help someone who is depressed or has suicidal ideas is to let them know they’re not alone, because feeling this way facilitates them making the decision to take their own life.

The Sanar Nicaragua Collective recommends weaving safe ties and support networks, reading the booklets they have produced to guide mutual and self-care practices during emotional crises, and always asking for help when it’s needed. The collective website lays out a series of resources including emergency phone numbers.