Nicaragua: Women «survive more than one pandemic»

On March 18, 2020, the first case of coronavirus was officialized in Nicaragua, four days after the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo ordered state workers and summoned their militancy to take to the streets of the capital, Managua, to march for the «Love in COVID-19 times».

The fact was condemned by the medical guild that called it «reckless», in front of a world that was confined to curb the contagions of the new coronavirus. This was the first in a series of actions in which the State of Nicaragua acted in a «negligent and irresponsible» way in the face of the pandemic, according to the Nicaraguan Centre for Human Rights (CENIDH). While epidemiologist Alvaro Ramírez and the Nicaraguan Association for Human Rights (ANPDH) have denounced a «viral genocide» over the health crisis and how the global coronavirus emergency in the Central American nation has been treated.

Four months after the first infected person was officialized, Nicaragua records 3,147 confirmed cases and 99 COVID-19-related deaths, according to the Ministry of Health (Minsa), an institution that has been reported by CENIDH, ANPDH and the medical guild to «make up statistics» and «hide information». Management is not new, women’s organizations have also pointed to this state practice regarding data related to sexist violence.

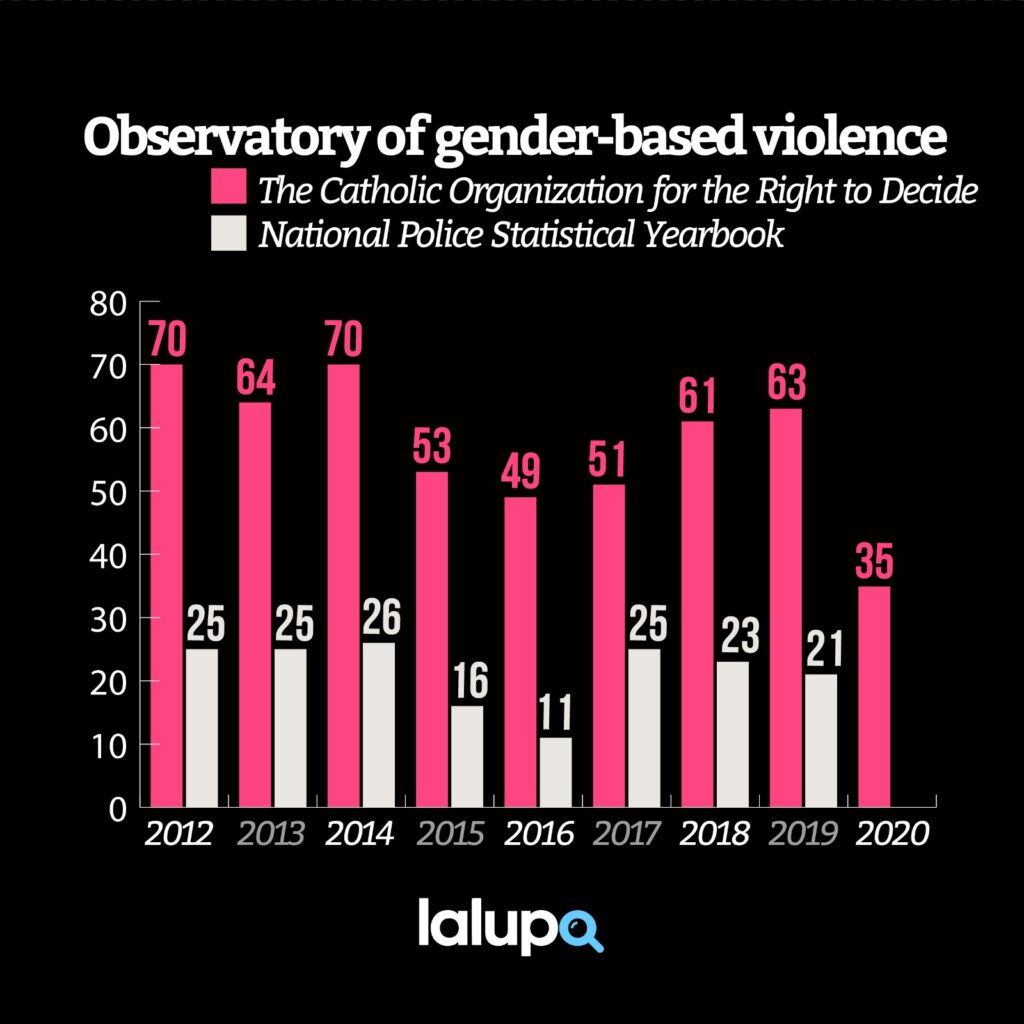

The Catholic Organization for the Right to Decide (CDD) the only NGO in Nicaragua that for more than 10 years maintains monitoring on sexist violence, counted a total of 35 femicides until June 2020. Two more than in 2019, which makes May the month with the most cases, eleven in total, of women victims of sexist violence registered in Nicaragua.

Martha Flores, director of CDD, believes that women in Nicaragua are surviving more than one pandemic: «sexist violence, COVID-19 and the sociopolitical crisis, and all in front of a sexist state, which violates rights and is absolutely responsible for the murders of women who still go unpunished,» she said.

Although in Nicaragua the authorities never decreed quarantine, civil society called for self-confinement to prevent the contagion that spread around the world, but paradoxically the site that protects them from the pandemic put their lives at risk to their assailants.

«Women are at home, which has become the most insecure place, including many girls and teenagers who were left under the control of potential aggressors,» said a Women’s Anti-Violence Network activist who avoids offering her identity in the face of persecution of those who are victims in the face of criticism of Ortega and Murillo’s human rights policies. In particular, since 2018, when the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) has pointed it out to commit crimes against «humanity» against the population. And in their case, for the allegations of the state of helplessness that women live in the country.

Another of her colleagues, who also offers these statements anonymously, added that in the midst of the pandemic «women are experiencing violence in different ways.»

The network member also explains, anonymously, that before the crisis about ten consultations of women victims of violence were received each month, through their social networks, but with the COVID-19 pandemic, cases have quadrupled and now they receive up to forty. «A growth that shows that women have their own pandemic. The face-to-face was effective in caring for women, but now it’s harder to care,» she mused.

Activists insist that «there is no trust in the state,» so the opening of women’s police stations, the first public body to address the reporting of women victims of violence, «does not have an impact on impunity and femicide cases in Nicaragua.»

The Women’s Police Stations were set up in 1993; in 2012 with the passage of Law 779 – Comprehensive Law Against Violence against Women, they were recognized, together with the Courts of Violence, under a comprehensive model of care with a gender-focused approach, but in 2015 Ortega disarticulated them. Now, in 2020, he has announced the reopening.

«In the first instance, we can not even say that the opening of these police stations is true because what women tell us is that they go to the Sandinista Police and they tell them that they cannot attend Women’s Police Stations, they say that there is no staff. That leaves women in total helplessness,» said María Teresa Blandón, a member of Nicaragua’s Feminist Movement, and a voice authorized to talk about it in Nicaragua , after years of struggle to vindicate women’s rights, and to have been a promoter of Law 779 – Comprehensive Law Against Violence against Women in 2012.

«The point is that there is no state action to protect these women, who before, during and after the pandemic have been living with their aggressors,» said Blandón, who questions the absence of a state strategy to prevent violence, «the fundamentalist discourse» that places the family above women’s lives and the use of state violence , persecution and repression against any dissenting voice in Nicaragua.

The recent release of more than 500 common inmates convicted of crimes of sexual violence and femicide, after benefiting from pardons given by the state during 2020, has also been a new blow to victims and family members seeking justice. Women’s rights defenders in the country agree that the decision represents a setback in women’s rights and the ability to obtain justice. They recall that the Executive has been repeatedly reported to the Standing Committee on Human Rights (CPDH) and the Nicaraguan Centre for Human Rights (CENIDH) for violation of fundamental rights.

«It is a situation of unprotection of women and impunity, because many of the aggressors are free,» Blandon questioned. Impunity in cases of femicide repeatedly affects victims. By 2020, for example, of the 35 cases registered by Catholics for the Right to Decide, only 15 have been prosecuted, while the remaining 20 have not yet been detained or prosecuted.

Human rights defenders also highlight the decree issued by the State in 2014 with which Law 779 – Comprehensive Law against Violence against Women was «denatured» by ignoring violence in the public sphere and limiting it to private, so the annual figures of women’s organizations vary markedly with those documented by the Sandinista Police.

In February 2017, Vilma Trujillo, 25 years-old, was burned at a stake with the aim of «taking out the demons», as directed by the evangelical pastor Juan Rocha, who purged a sentence of 30 years in prison, together with a group of settlers from the El Cortezal community in the Northern Caribbean of Nicaragua, who witnessed and collaborated in the fact.

The case was typified, by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, as appalling murder under the claim and denunciation of women’s organizations, who argue it was a femicide resulting from «misogyny, an absent state, sexist violence and religious fanaticism».

Since 2014, Sandinista Police statistics have seen a considerable decline in the recurrence of femicide in Nicaragua, in contrast to data from women’s organizations, in which the figures triple, but also in which 679 women victims of this crime have been counted over the past decade. An average between 50-70 annually.

The balance made by women’s rights activists and organizations on the situation of violence in the country shows a picture of absolute impunity for victims of sexist violence in Nicaragua, which in times of confinement intensified the lack of measures to care for those left at the mercy of their aggressor.

«We do not have a Women’s Police Station, nor do we have courts that adapt to the needs of women, particularly those living in rural areas or indigenous communities. The State has not had shelters for women who are at high risk. We also do not have prevention policies; nor emergency care for women; or reparation to those who are victims of violence. We don’t have reliable official data and we don’t have a child care policy, daughters of women who have been victims of femicide,» Bolandon summed up.

In 2007, when Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo returned to power 13 years ago, they assumed in their speech «a policy of gender and restitution of rights» that has been challenged by the results that, in practice, are checked with the victims, but which the State has defended with the incursion among the top 10 countries to be women, according to the Global Economic Fund where Nicaragua appears fifth after Iceland , Norway, Finland and Sweden.

«In Nicaragua we could not say that there is progress, in fact, we would have to say that the relative progress that was made before 2007 has been weakening,» Blandón said.

As a member of Nicaragua’s Feminist Movement, she explained that the model of comprehensive attention to gender-based violence that was launched in the governments prior to Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo has been «completely disjointed» until almost eliminated.

«What is present is a huge debt of the State of Nicaragua to the women who are victims of this pandemic by sexist violence and especially to children who have been left in orphanage,» she added.

Gloria felt nervous when she shared her story on «El Blog de la Denuncia» (The Complaint Blog), a Twitter and Facebook account that practices «social reporting» for victims of violence in Nicaragua, as a necessity to heal, but also to get «some justice» in a country where human rights organizations report that «violence against women is not a priority for the state.»

The day she read her stalker’s name on the social network, she realized that she was far from being the only one he had ever harassed and she told herself that «it was not possible for he (stalker) to go through life as if nothing, and affect other women.» Although she denounced under anonymity, she feared that she would be recognized and face retaliation because when she suffered the harassment she was left alone. His group of friends, in common with the stalker, preferred to believe him and not her. «I thought he was going to do something to me or he was going to realize it was me,» she said via phone call, in which it was agreed to keep his identity confidential for security.

They met when she was 17, now she’s almost 20. He drew very well and she became interested in his prowess in the role, but only saw him as a friend. While he misunderstood his interest and even asked her for «nudes» (intimate photos). To stop the abuse, he called her «fucking men’s illusion.»

Harassment upset his life. She was afraid. In college, as she walked down the aisles and he went behind, she felt frightened. «I even felt guilty,» she said that she already acknowledges that the abuser was him. Gloria is one of a hundred young women who during the coronavirus pandemic reported on social media, in Nicaragua, the violence of which she had been a victim. A visible phenomenon that various media outlets reported on the scale of complaints that were published daily in the account of «El Blog de la Denuncia».

«Quarantine has been like a way to find yourself and in this process of being found, the victims have been able to identify the abuses they have been subjected to and are therefore deciding to report,» she considered one of the young women behind the account who keeps her identity for fear of reprisals.

Violence is visible in the social media profile, abusers are exposed in search of a «social punishment» in the face of impunity that prevails in Nicaragua. «El Blog de la Denuncia» offers psychological or legal assistance with allied networks to continue the healing process and archives with evidence the complaints received that in the second quarter of 2020 alone amount to more than 300.

Lawyer Rosario Flores knows very well what it means to try to follow the path of justice in Nicaragua, as she has accompanied many women who report violence. In the context of the pandemic, she says that «there was an increase in violence against women, that for fear of spreading the SARS-CoV-2 produced by COVID-19 they do not go to police stations.»

Many have called them, but when they explain the route to follow, they immediately say phrases like «I’m going to wait until all this happens» or «when cases are diminished,» but they still endure,» she said.

The specialist in violence against women explains that the lack of trust in the institutions on the path to justice, and now the fear of contagion, affect the denunciations, but also the release of dozens of femicides and sexual abusers that the State liberates through pardons, without the perpetrators paying for their crimes , increases impunity in the country.

Flores believes that social media reporting relates to the fact that, in many cases, women do not have regular exits to free themselves from their aggressors. To that we add the stress, anxiety and anguish of the health emergency. Now they have more time to think and reflect on what happened, she added.

El Blog de la Denuncia (The Complaint Blog) continues to process more than 200 pending complaints, and Gloria tries to retake everything that, at one point, stopped in her life.

As of June 30 in Nicaragua, there were 35 femicides and 45 in frustration, of which only 15 have had access to justice.

Karla managed to tell him to calm down:

– «Don’t do it, please. For the children», she told him as she felt the blood flow. Her husband, 29 years old, had attacked her with a knife. Memories are constantly running over in this 26-year-old woman’s mind. She fails to pin down how that chain of violent events originated. The clarity of the movements that preceded the horror also do not flow. She remembers that she managed to look at her in the mirror and noticed that «the situation was serious.»

She asked a relative to call an ambulance. She waited and went to the hospital.

«As soon as I turned around to make a straw for the baby, I felt the lunges in my neck,» Karla said. After eleven years of marriage, Karla, like other women, says that she «never imagined her husband would get to that point» because he «used to make some scandals, unimportant lawsuits,» she said, trying to minimize the matter. They happened when he drank alcohol, saying crazy things, «jealousy included». He would always go to sleep and that’s where the conflict ended.

She regards herself as a strong-natured person. They lived in a family routine that included Sunday walks. Together, the five of them, the family.

That Monday, June 8, he called her. He asked her to pick him up at work, but she refused. She told him she was busy and to look for his own means to transport himself. Finally, he appeared around 7:00 p.m. He had been drinking. Upon arrival he began to «make scandals» at his dad’s house, who is his neighbor.

She went out to the door of the house and tried to persuade him. She told him to come in, calm down, go to sleep, but he ignored her. What Karla never thought was that in just a few minutes she would become a survivor of femicide in frustration in Nicaragua, where until May 30, 40 murders of women were counted.

While in the hospital, his relatives filed the complaint with the National Police, but when they arrived in search of her testimony, she chose not to report. Instead, she preferred to accept a mediation with whom had attempted to murder her.

When he saw her again, he wept and apologized. She told him she had no grudge or hatred.

«I forgive you,» she said. They won’t live together anymore, she assured. He swore to her that he didn’t remember the aggression that almost killed her. He excused the hesitation in alcohol and other substances he allegedly consumed, but his wife doubts it, and rather remains shocked by the fact that the man she trusted injured her and in that way.

Karla knows that she is a victim of sexist violence. She is aware that no lawsuit, «cuecho», justifies wanting to take someone else’s life. «I think only God can do that, but well, he has his punishment,» she said. «I forgive him to some extent, but go back to him, never, » she convincingly said.

Karla is a woman with long black hair and oval eyes. Her speaking shows certainness in his character. However, her look still reflects the pain of what happened. As she talks, she exhales, catches air and follows the talk. She reflects that it is hard to realize that the person with which she had lived for so many years was able to «treat me like this, the same one with which you had built a future, a life».

«You never stop knowing people,» she said. Nearly a month after that fateful June 8th in her life, her concern is beyond the wounds she suffered. She’s also not worried about what’s going to happen to the aftermath of the assault. All she’s got on his mind is her kids. Everyone depended on her husband, but he’s out of a job because they found out what happened to Karla and fired him.

«I’m seeing it bad,» added this mother, who lives in a town in northern Nicaragua, a country mired in a socio-political crisis that, coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, faces an increasingly precarious economy.

According to the Nicaraguan Foundation for Economic and Social Development (Funides), it is estimated that by 2020 poverty will grow by 36.9% in the Central American nation.

Women’s rights organizations and defenders have created mechanisms of solidarity and support to protect life from an adverse context that has been increased with the COVID-19 pandemic.

«That’s why it’s critical to have a friend, a neighbor, a family member, who can be turned to in complicated situations,» because «the more you’re isolated, the more vulnerable you are,» explained Sandra Arceda, head of the Colectivo 8 de Marzo in Esquipulas, Matagalpa.

The Colectivo 8 de Marzo has had three telephone lines attended by a lawyer and four human rights defenders, to provide comprehensive response and attention to women’s complaints. Communications are open 24 hours a day. Each call creates a file, follows up and, on a case-by-case basis, provides judicial accompaniment, even since the complaint is established. Despite these resources, Arceda considers the creation of a defense mechanism key.

«Women have to learn to seek pressure mechanisms to make the aggressor feel audited. For example, telling him he’s going to call his mom, make the complaint, warn him that there will be people willing to come to her aid if he tries to do something,» she said.

The specialist stresses the importance of having personal documents, correct addresses you could go to, phone numbers and clothing in case there is a need to leave for protection.

While the Women’s Against Violence Network has a rapid alert system that seeks the prevention of femicide. It consists of effective communication with the defenders, who, if necessary, transfer the woman to a shelter. Monthly they can enter two to three women, this because some who decide to go, in the end, give in to family or social pressure and stay at home. The Women’s Network is also offering counseling from virtual space. In addition, they support advocates with food packages and cleaning kits.

In the absence of an advocate in their territory that victims can attend, other alternatives that specialists recommend is to have a friend, church companion or neighbors. Mayte Ochoa, a member of Nicaragua’s Feminist Movement, also believes that security and protection plans are necessary.

«They should find a place where they feel safe, that they always have a phone on hand, something to warn with, that they have a bag ready with clothes, some money and necessary items in the moment of a crisis, that allow them to go out with their children in case of any emergency,» she said.

Women must identify their safe areas, but also their entrances and exits. They must know where they might be most harmed, where they are most at risk. However, the advice is that if you identify that your life is in danger, it is best to try to calm down, activists and NGOs agree.

____

*The names used in testimonials are pseudonyms.

* This article is part of the investigation Violence against women: The invisible pandemic, a transnational and collaborative project in which La Lupa participated in alliance with the media Te Lo Cuento News (United States), Expediente Politico (Mexico), Periódico laCuerda and Asociación La Cuerda (Guatemala), La Tribuna de Todos (Venezuela), and Revista La Brújula (El Salvador).