«The Little Granny», the mother of generations in Nicaragua

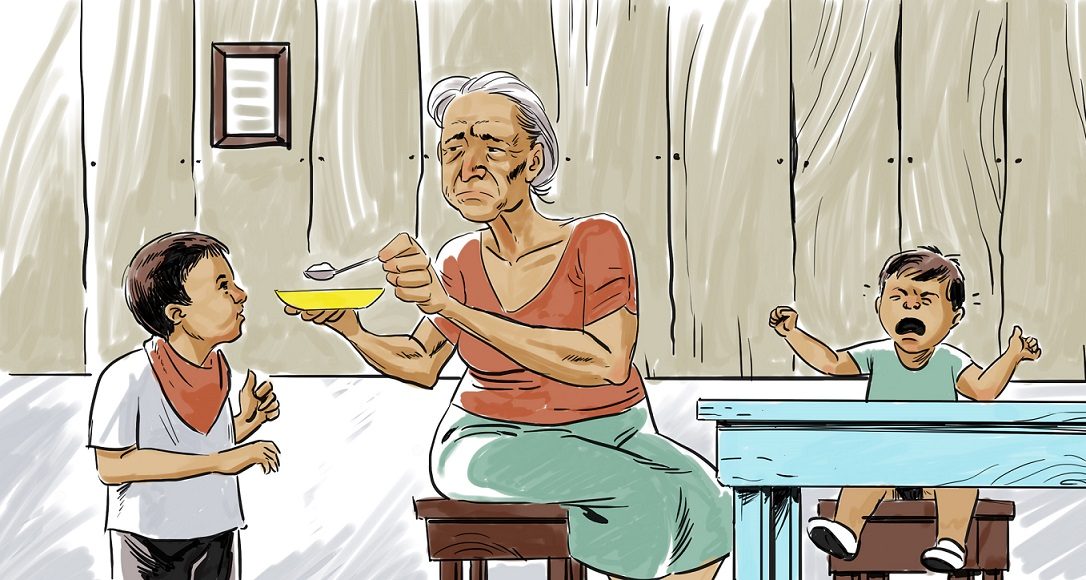

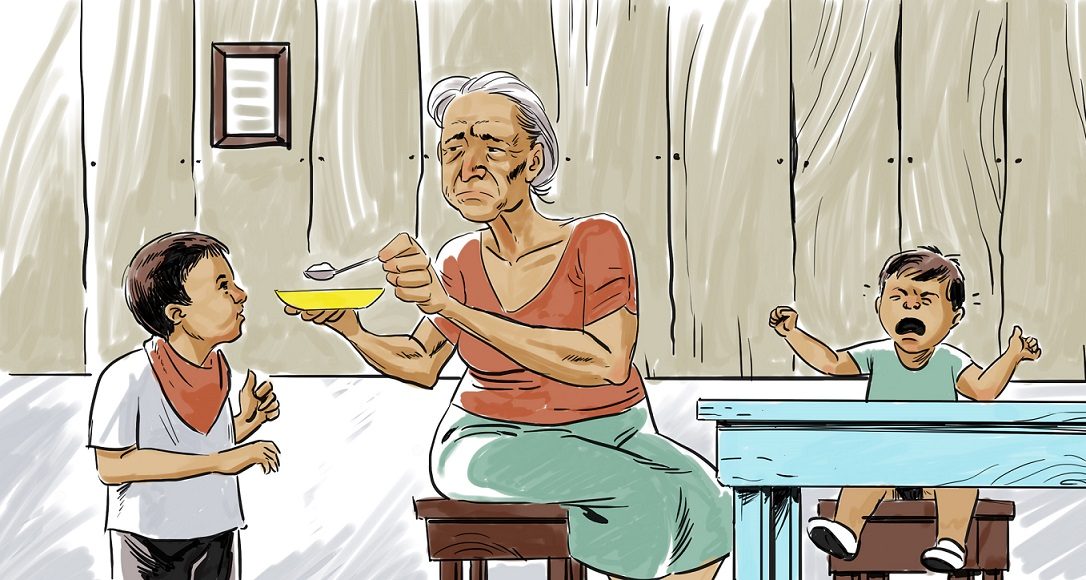

Grandmothers in Nicaragua play a fundamental role in care work, which means that these women repeat the processes of bringing up children over two and even three generations.

Grandmothers in Nicaragua play a fundamental role in care work, which means that these women repeat the processes of bringing up children over two and even three generations.

At 83 years old Angela Sequeira continues to raise children. She takes care of her great grandchildren of four and six years old, because her granddaughter, who was also brought up by her, chose to start a relationship with a new partner, leaving the children in her charge. This responsibility is something she wasn’t asked about, but she has taken it on because she says it makes her “sad to see the children going around from one place to another”. They’re not with their father because the children got used to this house. Their father visits them once in a while and helps out economically.

Angela is called “the little granny” in her family. She gave birth to 12 children, she has 18 grandchildren and 6 great grandchildren. In the family she is the centre of care work. One of her daughters migrated for work from Nicaragua to Guatemala more than 20 years ago in order to maintain her 6 kids, whom she left with Angela, but 3 of them were claimed by their fathers and brought up by them, while the remaining three stayed and were raised by her. She took care of them and ensured their education, but after a while she also had to take on their economic costs because her daughter died in Guatemala.

“They were left without a mother and father, so I took charge of them. I’m like a mother to them. They call me Mum. And a daughter of mine who has no kids has always helped me with their keep. Because as a domestic worker I earned very little”, Angela explained.

Until she was 81 this small and thin brown woman, with curly black hair, worked as a home help as a way of sustaining her family. Although she says she still has strength, she admits times are difficult and raising the children has changed. But the emotional connection with the grandchildren and great grandchildren is strong, which she says doesn’t allow her “to even think” of not continuing the work in caring for them.

“I feel so much love for my grandchildren, because they have stayed with me since they were very young. So I love them very much, as though they were my own children and I also love the little great grandchildren very mucho”, Angela says.

Grandmothers, most of them maternal grandmothers, take on the role of raising their grandchildren as a duty, based on the concept of “faithfulness, trust and commitment”, according to the study «The Second Mother»: the naturalisation of the circulation of care between grandmothers and grandchildren in transnational Latin American families .

The study reveals that this trust is centred on the fact that “the grandmother has already demonstrated her capacity to bring up children” which serves as a basic reference. This report is based on the reality of migrant mothers, but it is true that even when the mothers are in the country, most grandmothers end up taking on this care work because the economic situation doesn’t allow for this childcare service to be paid in most cases. Factors such as: work schedules, precarious salaries, paternal irresponsibility, the lack of effectiveness of state policies for childcare centres and the low levels of insertion of women in the formal labour market mean that grandmothers end up becoming the mainstays for childcare as the «the other mothers».

On one occasion the smallest grandson of Ana Mendoza, 60 years old, said to her «my pretty Mum is Pina and you are my other Mum». She tells us this with laughter, because it’s clear that one way or another children realise that their grandmothers are acting as mothers as well. She admits that she’s been a mother twice: the first time when she gave birth to her own children and the second when she raised her seven grandchildren.

“Being a grandmother means playing a double role, I’ve enjoyed it so much and I feel happy that my daughters have given me these grandchildren, although at the beginning I was angry because I wanted my daughters to study, to get ahead in their education without putting their foot in it. But well, what could I do about it? They put their foot in it too soon. They made the cake so I had to cook it and enjoy it too”, Ana remarks humorously.

Ana insisted that her daughters had to work so they didn’t go through what she did. She had been forced to leave her profession as a teacher because her husband wouldn’t let her work outside the home. “I wanted them to work so they could help me, and I would take care of the kids (grandchildren). I wanted them not to worry because their children would be in my hands. The most wonderful thing that I’ve experienced, and my daughters have said this to me, is that everything their children have become and that they themselves are, they owe to me and I feel really proud of that”, Ana says.

“The mother and the family can trace a direct shared bloodline from grandmother-mother-grandchild, and they associate this with unconditional loyalty”, the Second Mother study emphasises.

In her stage as a grandmother and carer Ana admits that not everything was love and self-sacrifice. She also had feelings of disappointment and stress, because the different stages of the children’s development often clash with the health issues faced by grandmothers as they age. But in her case she managed to find a balance because of her profession, which helped her cushion these processes. After looking after her grandchildren for more than ten years she migrated to Costa Rica for economic reasons and she assures us that the mark she left on the lives of her grandchildren will not easily be erased.

These benefits and costs to the grandmothers’ health from being involved in bringing up their grandchildren means, on the one hand, that they are at less risk of suffering from depression-related illness, neurologically degenerative problems or loneliness. On the other hand, attributing all of the responsibility for child rearing to grandmothers tends to generate anxiety, stress and high blood pressure for them, according to several health studies. In Nicaragua grandmothers tend to be younger than in other continents around the world, but this does not mean they should be exempt from closing their stage of child rearing.

Abi Urbina, a 56 year old grandmother is clear that her nine grandchildren give her a lot of joy, but this doesn’t mean that she’s open to being in charge of their full time care. “I’ve finished bringing up my daughters. Now they have to take on their own responsibilities, because if I take charge of their children, it’s bad for them. Afterwards their children will ask: ‘which is my real Mum? this one or the other one.?’ And that hurts. Changing nappies and giving them their milk isn’t hard. The hard thing is the upbringing”, Abi says.

She gets together frequently with her grandchildren, she looks after them on certain occasions, and she’s clear that the grandmother is considered to be the person of “maximum trust” for taking care of grandchildren. But she stresses that it is “under her rules” because she’s educating her grandkids in the same way that she brought up her daughters.

Any limit to the obligations, duties and work in bringing up grandchildren is unclear, because there is a fine line between this labour and a grandmother’s love and loyalty. This makes it difficult to create boundaries and a certain distance from the mothers’ responsibilities.

There is nothing registered in official statistics that indicates what percentage of grandmothers are taking charge of their grandchildren. What is certain is that it has been increasing steadily with the massive movement of migration, according to experts in this field.

The reality of bringing up grandchildren is that the commitment taken on by the grandmothers «is seen as work that is selfless, emotional, subjective and almost never paid, hence the feeling they are being used is inexistent because they are acting based on the focus of love», the Second Mother study explains.