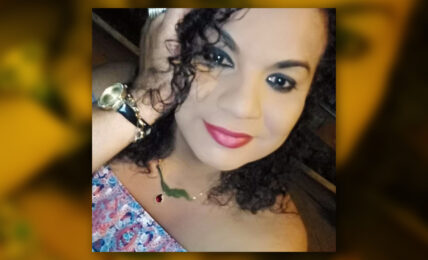

Trans women in a “grave situation of vulnerability and lacking state protection”

The state of impunity for violence against trans human rights defenders is a “clear reflection of the tolerance and normalization of these acts” with which this violence is treated by the state and wider society.