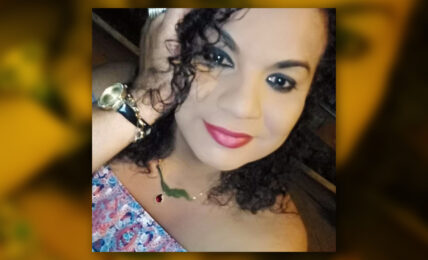

Being a mother in Nicaragua: Poverty, exclusion and bringing up children alone

Reconciling motherhood, work, personal space, and professional training makes it impossible for mothers when there is no co-responsibility from fathers, and a lack of support structures from child rearing and care.