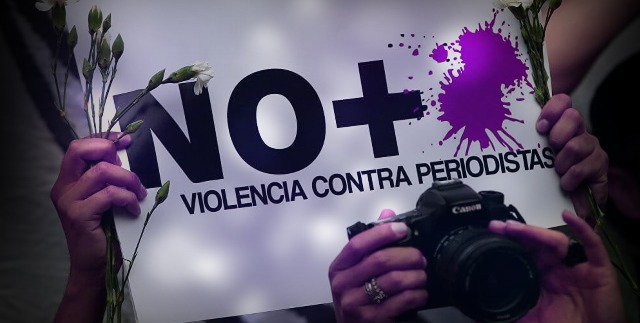

The year 2020 marked the close of an extremely violent decade for women in Nicaragua. More than 600 women were victims of femicide in a country that lacks public policies and strategies focusing in the defence of women and girls’ lives.

Despite indications at the beginning of the decade, in 2012, that violence against women might decrease under the Comprehensive Law Against Violence Towards Women (Law 779), which included opening more Women and Children’s Police Commissariats under the National Police, we closed the decades with «great setbacks» according to feminist organisations and activists.

María Teresa Blandón, Nicaraguan feminist and sociologist, clarifies that Law 779 was not a State initiative, but rather the result of work carried out by women’s collectives who elaborated the proposal. However, Blandon claims, the State grabbed that initiative, and it «distorted and weakened it».

“Instead of accepting the Law in it’s entirety as it had been proposed, the State grabbed it from out of our hands. Not satisfied by this alone, the State distorted it through detailing regulations that state the opposite of the Law itself. In other word, the State of Nicaragua essentially boycotted Law 799, which is a completely nonsensical”, she explains.

For Blandón, the State became complicit with the perpetrators of violence against women, not just by omission, but also directly by its actions. “We have enough evidence to say that the State of Nicaragua has become an accomplice over the last 14 years. The evidence is the following: the State violates the Law that the Parliament had approved; hides the gravity of the figures and presents false statistics to minimise the seriousness of this violence; it forces victims to mediate with their aggressors, thereby exposing them to further risks; and lastly, the State closes its doors to women so they cannot obtain justice”, she emphasised.

Feminist organisations denounced the gradual closing by the State, of the Women and Children’s Police Commissariats, which had been the first stop in the route to access justice for women victims of any type of machista (male supremacist) violence. Although the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo regime has been announcing their “reopening” since 2019, this has not been witnessed as positive by women’s rights defenders in their communities.

The closures of the Women and Children’s Police Commissariats meant the loss of an important space that women had won through their own struggle, states Martha Flores, Coordinator of Catholics for the Right to Choice (Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir CDD). She says the closures leave women and children even more defenceless.

“The people who provided assistance at the Women and Children’s Police Commissariats were specialised in the area, but when they disappeared, women had to speak to any police officer about what had happened; it was a backwards step. This perpetuated the impunity of aggressors and women’s distrust in making a complaint”, affirmed Flores.

By 2016, there were no Women and Children’s Police Commissariats open at all, recalls Maryce Mejía, National Liaison for the Network of Women Against Violence (Red de Mujeres contra la Violencia RMCV). As a consequence, a large proportion of the victims who were women from rural areas would go to the network members’ organisations looking for support. In 2020 the situation worsened with the self-confinement provoked by the Covid 19 pandemic, as many women were forced to live with their aggressors for longer, states Mejía.

“There was an increase in femicides in Latin America, but Nicaragua is a unique case because, in addition to the pandemic, we have multiple crises such as the deterioration of the justice system and the deterioration of human rights thanks to an indifferent and absent State. This has been a decade full of cruel statistics”, claims Mejía. She adds “the police is making femicides invisible because they are recorded as murders or aggravated robbery. This affects us a lot”.

Flores from CDD, an organisation that has been rigorously monitoring machista violence since 2011, pointed out that, as the “the original Law was tampered with”, the data that the State presents will never coincide with the records kept that women’s rights defenders have been keeping.

Following the reform, Ortega’s Police registers as femicide only those cases that happen in private spaces according to the regulation of Law 779, with Decree 42-2014 from the 31st of August 2014. It reads: «Femicide: Crime committed by a man against a woman in the context of interpersonal couple relationship and which resulted in the death of the woman…” The CCD and women’s organisations register cases according to what was established in the original Law 779 approved in 2012, which state as femicide as a crime that “result in the death of the woman, either in the private or the public sphere”.

To make matters worse, the 2014 reform allowed the perpetrators to mediate with victim of domestic violence, which put women at greater risk of femicide, and contributed to making the real statistics on violence and later femicide invisible.

All these problems are in addition to the lack of institutions to prevent, investigate or guarantee justice for the victims of machista violence.

Government indifference to violence

Blandón recalls that the work on prevention of violence has been carried out since the decade of the 80s, when there was a lot of resistance from most male leaders of the Sandinista government of that time. Today’s Orteguista version of the FSLN continues not to prioritise it. The transition government of the 90s started working in the creation of the Women and. Children Police Commissariats and there was a certain degree of support from the government in power, but it didn’t consolidate the system.

The sociologist recognises that historically women have been the ones to carry out most of the work, promoting awareness campaigns around gender violence; proposing to include the topic in the education curriculum in schools; creating support networks in support of the victims; demanding reparations for the damages and documenting the gravity of the violence, among other initiatives.

Flores from CDD points out that women’s organisations have ended up having to take on a role that should belong to the State. “The State is not committed to the lives of women. However, we are going to continue fighting despite the threats and attacks – because various organisations have already been closed, there is persecution against others, many people have had to go into exile, and the few of us who remain in the country will keep fighting”, she stated.

Mejía confirms the persecution that human rights defenders face in Nicaragua, evidenced in the Ministry of Interior’s refusal to provide the documentation and permits to which they have a right as civil organisations. “Many [organisations] have had their property stolen by the state, they have been confiscated, and in this context, it has been hard to work. Even so, we keep working and denouncing [these situations and the violence]”, she said.

Women human rights defenders agree that the coming decade brings many challenges around human rights and particularly 2021, as it is an election year. “An election year in which crime is increasing in general, especially as the Government freed over 20,000 common convicts, which means that a lot of weapons are circulating in the streets (…) 2020 was a year of tragedy”, Flores emphasised.

For these women, the first essential step would be the definitive departure of the Ortega-Murillo regime, considered to be a perpetrator of violence. After removing the obstacle that they represent, it will be necessary to “remove the machista, racist and homophobic structures that have become cemented into the [public] institutions”.

“I don’t want to be pessimistic but given that we closed 2020 with 71 femicides, if we make a prediction for the election year, with a new outbreak of Covid 19 and with an even heavier deterioration in institutional stability, the context for what’s coming is not favourable”, Mejía predicts.